[...] " There is no white picture. And there is no old picture. It is always a question of current experience and current perception." Rainer Borgemeister

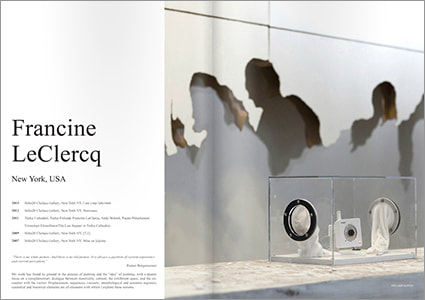

Francine LeClercq was born in Belfort, France.

She studied at The School of Decorative Arts of Strasbourg completing her education in interior architecture and fine arts with honors.

Her work has found its ground in the process of painting and in the “idea” of painting, with a deeper focus on a complementary dialogue between materiality, content, the exhibition space, perceptual process, and encounter with the viewer.

Francine LeClercq has had six solo exhibitions and has contributed work to more than one hundred group exhibitions mostly in the United States, but also in Europe and Asia.

She has had the privilege to see her works selected in national and international competitions by eminent curators and historians such as Peter Blum (Peter Blum Gallery), James Cuno (Art Institute Chicago), Susan Fisher Sterling (National Museum Women in the Arts) , Lynne Warren (Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago), Larry Thomas (San Francisco Art Institute), Steven Evans (Dia Foundation Beacon), Maxwell Anderson (Whitney Museum New York) , Eugenie Tsai (Brooklyn Museum), Judith Tannebaum (Institute of Contemporary Art of Philadelphia), Thom Mayne (Pritzler Prize 2015 recipient) and Janne Sirén (Albright-Knox Gallery), among others.

Her work has been included in museum exhibitions such as the Allentown Art museum (Allentown,PA), the Chelsea Art Museum, (New York, NY), the Holter Museum of Art (Helena, MT), the Islip Art Museum (Islip, NY), the Arnot Art Museum (Elmira NY), the Masur Museum (Monroe, LA), the CICA museum (Gimpo-si/ Gyeonggi-do, Korea) and the Rijksmuseum (Amsterdam, Netherlands).

Notable publications include "The Last Supper in Turku Cathedral: Francine LeClercq, Andy Warhol, Pauno Pohjolainen” published in conjunction with the exhibition organized for the 2011 European Capital Culture Events of Turku/Finland. Her work has also been reviewed in The New York Times, The New York Times Weschester, The Chicago Tribune, The Chicago Sun-Times, The Star-Ledger, The Allentown Morning Call, The Easton PA Express Times, The Boston Sunday, Octogon International, American Style, Arhitext International, Azimuts, The Dernières Nouvelles d’Alsace, Turum Sanomat, The Art Newspaper, Art Tribune, Observer, Blouin Artinfo as well as numerous national and international websites.

She works and lives in New York City.

She studied at The School of Decorative Arts of Strasbourg completing her education in interior architecture and fine arts with honors.

Her work has found its ground in the process of painting and in the “idea” of painting, with a deeper focus on a complementary dialogue between materiality, content, the exhibition space, perceptual process, and encounter with the viewer.

Francine LeClercq has had six solo exhibitions and has contributed work to more than one hundred group exhibitions mostly in the United States, but also in Europe and Asia.

She has had the privilege to see her works selected in national and international competitions by eminent curators and historians such as Peter Blum (Peter Blum Gallery), James Cuno (Art Institute Chicago), Susan Fisher Sterling (National Museum Women in the Arts) , Lynne Warren (Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago), Larry Thomas (San Francisco Art Institute), Steven Evans (Dia Foundation Beacon), Maxwell Anderson (Whitney Museum New York) , Eugenie Tsai (Brooklyn Museum), Judith Tannebaum (Institute of Contemporary Art of Philadelphia), Thom Mayne (Pritzler Prize 2015 recipient) and Janne Sirén (Albright-Knox Gallery), among others.

Her work has been included in museum exhibitions such as the Allentown Art museum (Allentown,PA), the Chelsea Art Museum, (New York, NY), the Holter Museum of Art (Helena, MT), the Islip Art Museum (Islip, NY), the Arnot Art Museum (Elmira NY), the Masur Museum (Monroe, LA), the CICA museum (Gimpo-si/ Gyeonggi-do, Korea) and the Rijksmuseum (Amsterdam, Netherlands).

Notable publications include "The Last Supper in Turku Cathedral: Francine LeClercq, Andy Warhol, Pauno Pohjolainen” published in conjunction with the exhibition organized for the 2011 European Capital Culture Events of Turku/Finland. Her work has also been reviewed in The New York Times, The New York Times Weschester, The Chicago Tribune, The Chicago Sun-Times, The Star-Ledger, The Allentown Morning Call, The Easton PA Express Times, The Boston Sunday, Octogon International, American Style, Arhitext International, Azimuts, The Dernières Nouvelles d’Alsace, Turum Sanomat, The Art Newspaper, Art Tribune, Observer, Blouin Artinfo as well as numerous national and international websites.

She works and lives in New York City.

Education

Master's Degree in Fine Arts, School of Decorative Arts Strasbourg-France 1989

Bachelor's Degree in Interior Architecture, School of Decorative Arts - Honor list- Rietleng prize

Awards, Prizes, Fellowship

2022 Grant Artists’ Fellowship • 2022 Grant LMCC Creative Engagement • 2021 Grant NYFA/Rauchenberg Foundation • 2021 Honorable Mention, Galerie Biesenbach, Cologne/Germany •2019 First Award International Emmentaler AOP, Milan, ITALY • 2018 long list, Aesthetica Art Prize UK • 2018 Shorlist, Hirosaki Art & Design Award, Hirosaki/Japan • 2017 International 2017 Rijksstudio Public Award, Rijksmuseum-Amsterdam, NL • 2015 Fellowship, Soho20 Chelsea Gallery, New York NY • 2014 Silver Prize, Art Ascent Publications • 2012 International Award, Artists Wanted, SCOPE NY • 2011 Shortlist: She disappeared into complete silence, rereading a single work by Louise Bourgeois, De Hallen Haarlem/NL • 2007 1st Prize Second International Showdown, Saatchi Online Gallery UK • 2005 3rd Prize Chicago Prize International Competition • 2005 3rd Prize McCormick Freedom Museum International Public Art Competition•2004 1st Prize Anna 33, The Holter Museum of Art, MT •1989 Ritleng Prize, Strasbourg/France •1988 1st Prize Public Art Competition, Fessenheim/France •1986 2nd Prize of Painting, 11th Festival of Painting and Sculpture, Belfort/France •1984 3rd Prize of Painting, 9th Festival of Painting and Sculpture, Belfort/France •1983 3rd Prize of Drawing, 8th Festival of Painting and Sculpture, Belfort/ France

Solo Exhibitions

2015, 2012, 2009, 2007, 2003, 1999, Soho20 Chelsea Gallery, New York NY

2/3 persons Exhibitions

2012 Francine LeClercq, Jason Peters, Laetitia Soulier, See Gallery, Long island City, NY

2012 Francine LeClercq and Lauren Greewood, Crevice Gallery, Provincetown, MA

2011 Francine LeClercq, Andy Wahrol, Pauno Pohjolainen, Turku Cathedral, Turku/ Finland

2022 Public Project: Covid-19 Pencil Tracker, founded by LMCC (lower Manhattan Cultural Center)

Museum Exhibitions AND National and International Juried Exhibitions

• 2023 Maake Project Annual, State College, PA • 2022 Painting in the New Abnormal, Contemporary Art Chronicle • 2021 Media & Material, Dodomu Gallery, Brooklyn NY• 2019 No Image, CICA Museum, Gimpo-si/ Gyeonggi-do, Korea •2019 Glitches & Deffects, Millepiani Gallery-Roma, ITALY • 2018 55th Annual, Masur Museum, Monroe LA • 2017 International Rijksstudio Award Exhibition, Rijksmuseum-Amsterdam, NL • 2016 Concept, CICA Museum, Gimpo-si/ Gyeonggi-do, Korea • 2014 74th Regional Exhibition, Arnot Art Museum, Elmira NY • 2013 International 56th Annual Exhibition of Contemporary Art, Chautauqua Institution, Chautauqua, NY • 2013 Working It Out, The Painting Center, New York NY • 2012 Distance, Grady Alexis Gallery, NY • 2011 Personal. Spaces, Crossing Art Gallery. Queens NY • 2009 Image& Word, TAC (The Art Center) Highland Park, IL • 2007 Metro25, CWOW (City Without Walls) Newarck, NJ • 2007 Access: A feminist perspective, Rhonda Schaller Gallery, New York NY • 2006 Still Life, The Islip Art Museum, NY• 2005 The Chicago Prize, Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago, IL • 2005 New Directions, Barrett Art Center NY • 2005 McCormick Freedom Art Competition, McCormick Freedom Museum, Chicago/IL • 2005 An Art Critic Choice, Studio Gallery, Washington DC • 2004 Anna 33, The Holter Museum of Art, MT • 2004 Outside the box, Robert Schonhorn Ats Center, NJ • 2002 Ten Contemporary Artists, 5 x 2 part II, Allentown Art Museum, PA •2001 Breaking the Rules, Katonah Art Museum, Katonah NY • 2001 National Prize Show, Cambridge Art Association, Cambridge, MA • 2000 27th Juried Show, Allentown Art Museum, Allentown, PA

Other Group Exhibitions

2024 Meta Group Show, Alfa Gallery+ ARTSY•2023 Alfa -Art Basel, Alfa Gallery+ ARTSY• 2023 Abstraction In Action, Alfa Gallery + ARTSY • 2017 Unauthorized SFMOMA Exhibitions Project • 2016 Platform/Platvorm, Melkweg Expo Amsterdam NL • 2016 What Is and Never Was, Parenthesis Gallery, Chicago, IL • 2015 Outside the White Cube, Manila /Philippines • 2014 Are We Already Gone?, Flickelab New York NY • 2013 Relational Ground: Defying the Status Quo, Soho20 Chelsea Gallery, New York NY • 2012 SCOPE New York • 2010 The Dinner Table and Feminist Influences, AIR Gallery, New York • 2008 Make Me An Offer, The Illinois Institute of Art, Chicago IL • 2008 Circulation, Gallery Kunstler, Rochester NY • 2008 The Hague Red Cross Exhibition, Nuithus Centre, The Hague/ NL • 2007 PAWNSHOP, e-FLUX, New York • 2006 Ideas, Images,structures, Soho20Chelsea Gallery, New York • 2005 Public process for public architecture, Chicago Architecture Foundation, Chicago/IL • 2003 Red, Gallery 218, Milwaukee WI •2003 New/ New Old, Evolution, Conceptual Links, Soho20/Chelsea, New York •2003 International Octogon Exhibition, Romanian Cultural Center, New York •2002 International Biennial III, Parc des Expositions, St Etienne/France

Book

“Viimeinen Ertoollinen; The Last Supper in Turku Cathedral: Francine LeClercq, Andy Warhol, Pauno Pohjolainen”, Perttu Ollila, Publisher Turun ja Kaarinan seurakuntayhtymä 2011, 137 pages,

Selected reviews and interviews

Note: list edited for length . Latest features include articles in Blouin Art info, The Art Newspaper, Art tribune, Observer, Designboom

Current: "Embroidered Surveillance", DesignBoom Magazine, March 2024

• “IDENTITEIT”, Beeldende Vakken 2019, Cito Instituut voor Toetsontwilleling, Netherland • Figen Girken, “Çağdaş Sanat ve Yeniden Üretim”(“Contempory Art and Reproduction”), HayalPerest Kitap Publisher, 2018 • Murze Magazine issue 8 Portraiture, Reality and Change, 2018 • Peripheral ARTeries Magazine, Biennial Edition 2017, Cover and interview p.4-28, 2017• ART REVEAL MAGAZINE (Finland), Cover and interview p.46-51, 09/2016 (ISBN ISBN 9781367293564) • PLATFORM/PLATVORM (Netherlands), issue No.2, December 2015 •Tatiana Istomina, Francine LeClercq: I Am your Labyrinth, Metaleptic Stories, June 7, 2015• Ali Soltani, Francine LeClercq, Eutopia Volume 3, June 2015 • Claire Obry, Francine LeClercq: I Am Your Labyrinth, French Winck, June 10 2015 • Laomi Lake, Francine LeClercq at Soho20 Chelsea Gallery, French Culture, May 2015 • Ana Bambic Kostov, Francine LeClercq, Art Ascent and Litterature, August 2014, pp12-15 • Anthony Bannon, In VACI"s 56th Annual, A quiet confident sense of excellence, The Chautauqua Daily, 07/13 • Paige Cooperstein, Albright-Knox director brings Nordic influence to Chautauqua's 56th Annual , The Chautauqua Daily, June 24, 2013• NY ARTS MAGAZINE, “Narcissism in Black”, October 2012 CREATIVE QUATERLY#27, September 2012 • FLASHBACK 2011, Photograph book, Turku 2011 Foundation • Pirkko Holmberg: “Uskonnollista Vai Nykytaidetta?”, Mustekala Magazine/Finland 07/ 2011• Santeri Seessalo: “Andy Warholin viimenen ehtoolinen” (“The last supper of Andy Warhol”), Turkulainen/Finland 04/2011• Lars Saari: “Nykytaidetta kirkkotilassa” (“Contemporary Art and Churches”), Turun Sanomat/Finland, 07/ 2011• Perttu Ollila: “Viimeisen ehtoollisen kattaus Turun tuomiokirkossa” (“The Last Supper table setting in Turku Cathedral”), TAIDE DESIGN No.2011/03/>p.106 • Erika Rönngård: “Modern nattvardskonst i medeltida miljö”(“Modern Art in Medieval Setting”), Kyrkpress/Sweeden 06/2011 • Lasse Raitio: “Neljä tulkintaa viimeisestä ehtoollisesta” (“Four interpretations on The last Supper”), Turun Sanomat/Finland April 16, 2011• Maria Thollix: “Warhol i domkyrkan”, Abo Underrattelser/Finland April 16, 2011• Artist Profile: Francine LeClercq, CREATIVE QUATERLY #18, April 2010 • Valérie Robert: “Quand le film raconte l'image. Variations cinématographiques autour de le Cène de Leonardo Da Vinci”, Les Cahiers de Narratologie 2009 (Switzerland)

• Deborah Baldwin, Artists In Residence, Habitats, The New York Times, 11/16/2008 • Dan Bischoff, Working small but thinking big”, The Star-Ledger 11/30/2007 • Benjamin Genocchio, “ Objects at Rest” Review: "Stilled Life"/Islip Museum, The New York Times 07/22/2006 • Kevin Nance, architecture critic “ Idea for city's water tanks generates award” Chicago Sun-Times 10/27/2005 • Blair Kamin “ World's designers aim at tanks” Chicago Tribune 10/27/2005 • Nancy Maes “ Can water tanks be art” Chicago Tribune 11/04/2005 • Blair Kamin“ Invention can be a double-edged sword” Chicago Tribune 10/30/2005 • Charles Storch “ Bill of Rights inspires artwork” Chicago Tribune 07/2005 • Lara Allison “ Exhibit showcases monumental debates” Chicago Tribune 04/2005 • Charles Storch “ Finalists named for sculpture at Tribune Tower museum” Chicago Tribune 04/2005 • Ali Soltani “ The [Un (for) seeable] Paintings of Francine LeClercq” Arhitext International 2004 • Dr. Livio G. Dimitriu: “The Unbearable Lightness of Tectonics”, Arhitext International 10/2004 • Ali Soltani “The Painting and the Gorgon, a reading onto the work of Francine LeClercq”, Arhitext #9/2003 • Kenneth Endick “Contemporary art inspires contemplation” Easton PA Express Times. 01/11/02 • Dominick Lombardi "Exploring the gamut of contemporary art", Review: “Breaking the Rules”, Katonah Museum, New York Times Weschester 06/17/01

• Cate McQuaid, review: National Prize Show, Boston Sunday Globe 07/08/01 • Geoff Gehman “Works unnerving to nervous pace at museum show” The Allentown Morning Call. 12/06/01• Ali Soltani “Francine LeClercq/ An Odyssey”, Octogon International #3/2000 p.25, 26, 27

PeripheralARTeries Magazine meets Francine LeClercq

Cover and interview with curators Josh Ryders, Dario Rutigliano and Melissa C. Hilborn

July 2017

Artist Francine LeClercq’s work grounds in the process of painting and the “idea” of painting, with a deeper focus on a complementary dialogue between materiality, content, the exhibition space, and the encounter with the viewer. Addressing the viewers to a multilayered visual experience, her body of works that we’ll be discussing in the following pages, successfully attempts to trigger the viewers’ perceptual parameters walking them through the liminal area in which perceptual reality and the realm of imagination find a consistent point of convergence. One of the most impressive aspects of LeClercq’s work is the way it accomplishes the difficult task of inquiring into the notions of displacement, sequences, viscosity, morphological and semantic registers, curatorial and historical elements: we are very pleased to introduce our readers to her stimulating and multifaceted artistic production.

P: Hello Francine and welcome to Peripheral ARTeries: we would start this interview with a couple of questions about your multifaceted background. You have a solid background and after having graduated with a Bachelor’s Degree in Interior Architecture you nurtured your education with a Master’s Degree in Fine Arts, that you received from the School of Decorative Arts, in Strasbourg: how did these experiences influence the way you currently conceive your works? And in particular, how does your cultural substratum inform the way you relate yourself to art making and to the notion of beauty?

FL: Hello and thank you for having me.

I expressed interest for drawing and painting at a very early age and was encouraged to develop my skills through intensive training in private studios and at the Municipal Art School of Belfort. Soon after my graduation, I received full scholarship for the School of Decorative Arts in Strasbourg. My answer to the exam committee for why I wanted to enroll in the interior architecture department was that “I needed to solve problems.” I don’t recall having had drafting or construction courses and later found myself quite unequiped when I did have to do my first professional internship in an architecture office, but what I learned was the ability to expose problems. I soon realized that if I were to go beyond an utilitarian discipline like architecture, I could create questions without having to offer a permanent solution. This notion of permanence, or rather its antonyms such as variability, instability, alterability and fluidity are the core of my work as they imply a constant remise en cause.

And this brings me to my (current) conception of beauty, constantly debating Augustine’s question of “whether things are beautiful because they give delight, or whether they give delight because they are beautiful”, or simply put, between the effect or the origin of beauty. Having had a classical education, I can’t deny my appreciation for harmonious proportions sometimes expressed in mathematical ratios i. e. the Golden Section or the canonical sculpture, but these place beauty as something purely objective and I must concede to the emotional effect of beauty, often associated with pleasure. A perfect balance is when I neither attribute beauty exclusively to the object or the subject, but to the relation between them and even more also to the situation and environment in which they are both linked.

The question is, can we still speak of the aesthetic experience in terms of beauty-that is a set of established criteria to judge a work? What I find more attractive, is not beauty per se, but the parameters that define it.

P: Your works convey a coherent sense of unity, that rejects any conventional classification. Would you like to tell to our readers something about your process and set up? In particular, are your works conceived and created gesturally, instinctively? Or do you methodically transpose geometric schemes?

FL: Though I have provided images that at first glance seem to fall into the category of installations, and as you have pointed out, my artistic production also entails singular paintings, objects, and architecture. And while the works share visual similarities, I can’t speak of a formula or a “one size fits all” approach, but of instead of methodology where specific procedures solve different problems within the scope of a particular discipline. To give an example with painting, it is the very material constructs essential to the becoming of the work (the stretcher, canvas and paint) that directly dictate their own creation, whether in the “catalytic”works (1), where, under gravity and repetitive rotations, paint drips frame the edges of the canvas, or in the “DNA” series (2), through incision in the canvas, leaving the paint in a kind of suspended viscid state.

In all cases, my creative process is always an interplay between conscious and unconscious, from investigations within the accumulation of intellectual resources out of which ideas emerge, to a sudden intuitive feeling of “obviousness” derived by a culmination of associations that will in turn, have to be validated in the later construction of the work.

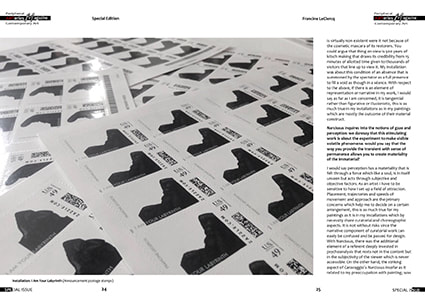

P: For this special edition of Peripheral ARTeries we have selected [3:2] (3). What has at once captured our attention of your inquiry into the notion of art as the moment of mutual dependency fermented by an active participation of the senses is the way you provided the visual results of your analysis with autonomous aesthetics: when walking our readers through the genesis of [3:2] would you tell us your sources of inspiration? And how did you select your subjects?

FL: The title of this work, [3:2], refers to the standard ratio found in camera and mobile devices LCD screens, effectively (in a sense) the new format of our perception. The small rectangular cells, liberated from the wall by cylinder spacers, are coated with a layer of thermochromic paint forming an opaque film. Filling the gallery’s walls, the scenario evokes the image of a vaporized display of memories scattered about like gas particles in suspense. The paint has the quality of becoming transparent with the increase in temperature passed through touch as spectators are encouraged to place their hands on the cells, revealing a myriad of old photographs belonging to the gallery’s past. Utterly depandant upon the visitor, the pieces can open like an album of universal memories, or remains absolutely abstract and unapproachable. Citing the exact measure of our portable mirrors and opposing analogue photographs to them, the works via the concept of traditional painting, expose the ephemeral nature of the novel perception. Furthermore, it asks to challenge the role of the artist as an image maker by transferring it to the viewers. Hence the gallery’s classic role as a match making box between the subject and the object, the see-er and the see-ee, employed to facilitate a tête-à-tête with this contemporary condition and restore, however temporarily an atmosphere of sensation or the sensible.

P: Your works address the viewers to challenge their perceptual parameters and allow an open reading, with a wide variety of associative possibilities. The power of visual arts in the contemporary age is enormous: at the same time, the role of the viewer’s disposition and attitude is equally important. Both our minds and our bodies need to actively participate in the experience of contemplating a piece of art: it demands your total attention and a particular kind of effort—it’s almost a commitment. What do you think about the role of the viewer? Are you particularly interested if you try to achieve to trigger the viewers’ perception as starting point to urge them to elaborate personal interpretations?

FL: The viewer is primarily a conscious subject without whom, existence/ any existence has no meaning simply because the relational field for the thing to be sensed doesn’t exist, a space that opens or is impinged upon the presence of the viewer; in this respect whether in my paintings or installations I always strive to locate the viewer not as an outsider but as an encoded other whose role and thingness is constantly shifting, in other words as mediums go, the spectator is very much a material component of the work. I am always fascinated how the work changes in the presence of one or a number of people. With one individual the work is relatively fixed, as the number increases, it is much more diffused like the swimming décors of Matisse- but I don’t mean that in a general sense, the decision to place a work on view requires a bird’s eye view of the situation that is being set up, a conceptual knowledge of the totality of the work that supersedes everything else, the question is how this knowledge is imparted, or at what critical moment the viewer finds itself in the presence of the work, and more importantly at what point do they merge and become one; in other words, by internalizing the viewing subject, the work seizes to be a ‘look at’ and opens itself to its engulfing exteriority- metaphorically speaking, if there is a narrative quality to grasp the internal logic, then the work is a door from where the perceiving subject steps out and perceives itself being perceived.

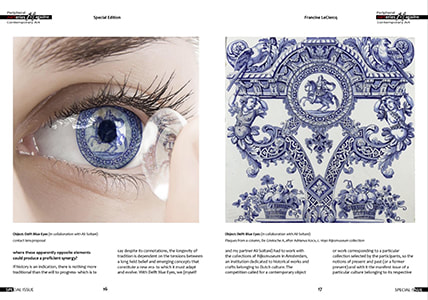

P: We like the way Delft Blue Eyes (4) challenges an inner cultural debate between heritage from the past and traditions that carry on to this day: despite the reminders to traditional figurative approach, your works is marked out with a stimulating contemporary sensitiveness. Do you think that there’s still a contrast between Tradition and Contemporariness? Or there’s an interstitial area where these apparently opposite elements could produce a proficient synergy?

FL: If history is an indication, there is nothing more traditional than the will to progress- which is to say despite its connotations, the longevity of tradition is dependent on the tensions between a long held belief and emerging concepts that constitute a new era- to which it must adapt and evolve. With Delft Blue Eyes, we (myself and my partner Ali Soltani) had to work with the collections of Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, an institution dedicated to historical works and crafts belonging to Dutch culture. The competition called for a contemporary object or work corresponding to a particular collection selected by the participants, so the notions of present and past (or a former present) and with it the manifest issue of a particular culture belonging to its respective epoch, defined the basis of the work- that is the insertion of something in time which is an uninterrupted continuum within the full breadth of unfolding historicity. Perceived in this way history is no longer a compilation of linear succession of distant events, and instead an instantaneous landscape of intensities marked by the peculiarities of a given time that could be interchangeably linked. We took the image of 17th Century Delftware plaques which was the high craft of the period and grafted it onto non-prescriptive contact lenses. Both are products that have flourished because of high demand and thus emblematic of their respective culture- on the one hand a product of the Dutch Golden Age characterized by its distinctly tactile quality attained through the manual manipulation of firing and glazing earthenware- and on the other hand the intricacies of an impalpable digital age represented by a technological veil on the iris that like a chameleon as it were has become one with the object it is fixated on. Thus in the implicit fragility of a crossbred porcelain gaze as the site of perceptual happenstance, a reference was made to Marcel Duchamp’s notion of non retinal art and the Readymades both with respect to chance encounters and choice, and more importantly by the realization that the navigational path of modernity to progress doesn’t have to be one way, nor straight. What is at stake is the notion of progress itself.

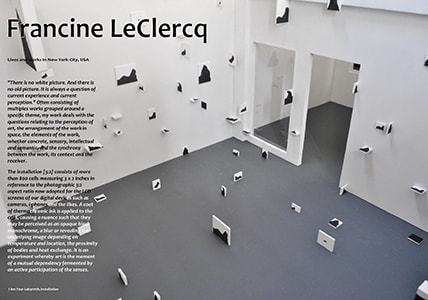

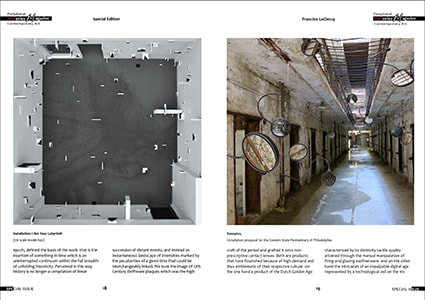

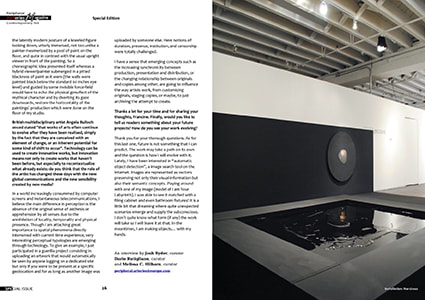

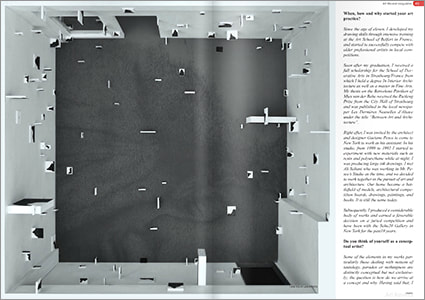

P: I Am Your Labyrinth (5) provides the viewers with an intense, immersive experience and as you have remarked in your artist’s statement, your work focuses on a complementary dialogue between materiality, content, the exhibition space, and the encounter with the viewer: how do you see the relationship between public sphere and the role of art in public space? In particular, how much do you consider the immersive nature of the viewing experience and how you see the relationship between environment and your work?

FL: It seems to me that with the advent of the internet, the domain of public sphere is shifting or I should say expanding from the exclusively collective spaces of streets and urban squares to the stealth realm of domestic life where it reincarnates as the virtual space of networks and the world wide web receding into a labyrinthine pixellation of some kind of media screen. On the other hand the casual urbanite is entrapped within a maze of partitioned institutions each catering to a different purpose with relative sufficiency, but the notions of the institution and the public remain at large and whether or not our relationship with art in this artificial construct is tenable. In this sense the reappearance of Ariadne as the eternal liberator that could offer us a way out, served as a narrative geared towards a critic of how we see and experience art and the whole machinery of its production. As the gallery space was being shared with another artist the construction of a 1:6 scale model of the gallery space not only compensated for the remaining area for the fully site specific installation, it effectively served as a gyrating crux through which the white cube imploded and expanded out, and blurred the normative distinctions between the perceptual and conceptual space. Similarly by incorporating the administrative aspects of the gallery and its reliance on infrastructure in organizing an event such as the invitation cards which were numbered and the mailing stamps that depicted my images of Ariadne, an attempt was made to reach beyond the confines of the gallery space and re-frame our notions of perception through an installation at large.

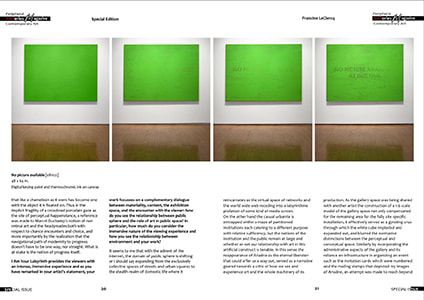

P: Despite to clear references to perceptual reality your visual vocabulary, as reveals the interesting Mise en [s]cène (6), has a very ambivalent quality. How do you view the concepts of the real and the imagined playing out within your works? How would you define the relationship between abstraction and representation in your practice?

FL: If you consider the notion of mise-en scène in set design, it consists of the staging of actors on a scene where its formal qualities is founded on a narrative that follows the telling of a story, a theatrical or cinematic likelihood that is mounted in front of a seating audience some distance away. What it shares with other arts is that it posits itself to be seen, designed to captivate the attention of a viewer, it relies in more or lesser degrees on some credence that is conveyed by content, structure, or both. What interests me however is the cross section of this business of viewing, that (emotional) field that holds the two parts, the viewer and the viewed glued to each other. To speak of the real, some years ago I saw a film by Abbas Kiarostami called Shirin in which the camera is turned to the viewers watching some epic Persian love story. We, the real viewers see the movie directly but we perceive the love story obliquely, guessing, through the contorted faces of its audience. I said real because at the end that is all there is, the question isn’t so much what we are looking at, rather how we are seeing it which I take to be the mise-en scène in my work. The Mise en [S]cène that you refer to, in its literal translation: To put on view- with a bracketed “S” before cène- (French for Il Cenacolo /The Last Supper of Leonardo daVinci), is an installation consisting of six panels that roughly add up to the same size of the original mural which literally flaked off and is virtually non existent were it not because of the cosmetic mascara of its restorers. You could argue that thing on view is 500 years of kitsch making that draws its credibility from 15 minutes of allotted time given to thousands of visitors that line up to view it. My installation was about this condition of an absence that is summoned by the spectator as a full presence to fill a void as though in a séance. With respect to the above, if there is an element of representation or narrative in my work, I would say as far as I am concerned, it is tangential rather than figurative or illusionistic, this is as much true in my installations as in my paintings which are mostly the outcome of their material construct.

P: Narcissus (7) inquires into the notions of gaze and perception: we daresay that this stimulating work is about the experiment to make visible volatile phenomena: would you say that the way you provide the transient with sense of permanence allows you to create materiality of the immaterial?

FL: I would say perception has a materiality that is felt through a force which like a soul, is in itself unseen but acts through subjective and objective factors. As an artist I have to be sensitive to how I set up a field of attraction. Placement, trajectories and speeds of movement and approach are the primary concerns which help me to decide on a certain arrangement, this is as much true for my paintings as it is in my installations which by necessity share curatorial and choreographic aspects. It is not without risks since the narrative component of curatorial work can easily be confused and be passed for design. With Narcissus, there was the additional element of a referent deeply invested in psychoanalysis that rests not in the content but in the subjectivity of the viewer which is never accessible. On the other hand, the striking aspect of Caravaggio’s Narcissus insofar as it related to my preoccupation with painting, was the latently modern posture of a kneeling figure looking down, utterly immersed, not too unlike a painter mesmerized by a pool of paint on the floor, and quite in contrast with the usual upright viewer in front of the painting. So a choreographic idea presented itself whereas a hybrid viewer/painter submerged in a pitted blackness of paint as it were (the walls were painted black below the standard 60 inches eye level) and guided by some invisible force-field would have to echo the physical genuflect of the mythical character and by diverting its gaze downwards, restore the horizontality of the paintings’ production which were done on the floor of my studio.

P: British multidisciplinary artist Angela Bulloch once stated “that works of arts often continue to evolve after they have been realized, simply by the fact that they are conceived with an element of change, or an inherent potential for some kind of shift to occur”. Technology can be used to create innovative works, but innovation means not only to create works that haven’t been before, but especially to re-contextualize what already exists: do you think that the role of the artist has changed these days with the new global communications and the new sensibility created by new media?

FL: In a world increasingly consumed by computer screens and instantaneous telecommunications, I believe the main difference in perception is the absence of the original sense of aisthesis or apprehension by all senses due to the annihilation of locality, temporality and physical presence. Though I am attaching great importance to spatial phenomena directly interwined with current time experience, very interesting perceptual typologies are emerging through technology. To give an example, I just participated in a guerilla project consisting in uploading an artwork that would automatically be seen by anyone logging on a dedicated site but only if you were to be present at a specific geolocation and for as long as another image was uploaded by someone else. Here notions of duration, presence, institution, and censorship were totally challenged.

I have a sense that emerging concepts such as the increasing synchronicity between production, presentation and distribution, or the changing relationship between originals and copies among other, are going to influence the way artists work, from customizing originals, staging copies, or maybe, to just archiving the attempt to create.

P: Thanks a lot for your time and for sharing your thoughts, Francine. Finally, would you like to tell us readers something about your future projects? How do you see your work evolving?

FL: Thank you for your thorough questions. As for this last one, future is not something that I can predict. The work may take a path on its own and the question is how I will evolve with it.

Lately, I have been interested in “automatic object detection”, a image search tool on the internet. Images are represented as vectors preserving not only their visual information but also their semantic concepts. Playing around with one of my image (model of I am Your Labyrinth), I was able to see it matched with a filing cabinet and even bathroom fixtures! It is a little bit that dreaming where quite unexpected scenarios emerge and supply the subconscious.

I don’t quite know what form (if any) the work will take so I will leave it at that.

Cover and interview with curators Josh Ryders, Dario Rutigliano and Melissa C. Hilborn

July 2017

Artist Francine LeClercq’s work grounds in the process of painting and the “idea” of painting, with a deeper focus on a complementary dialogue between materiality, content, the exhibition space, and the encounter with the viewer. Addressing the viewers to a multilayered visual experience, her body of works that we’ll be discussing in the following pages, successfully attempts to trigger the viewers’ perceptual parameters walking them through the liminal area in which perceptual reality and the realm of imagination find a consistent point of convergence. One of the most impressive aspects of LeClercq’s work is the way it accomplishes the difficult task of inquiring into the notions of displacement, sequences, viscosity, morphological and semantic registers, curatorial and historical elements: we are very pleased to introduce our readers to her stimulating and multifaceted artistic production.

P: Hello Francine and welcome to Peripheral ARTeries: we would start this interview with a couple of questions about your multifaceted background. You have a solid background and after having graduated with a Bachelor’s Degree in Interior Architecture you nurtured your education with a Master’s Degree in Fine Arts, that you received from the School of Decorative Arts, in Strasbourg: how did these experiences influence the way you currently conceive your works? And in particular, how does your cultural substratum inform the way you relate yourself to art making and to the notion of beauty?

FL: Hello and thank you for having me.

I expressed interest for drawing and painting at a very early age and was encouraged to develop my skills through intensive training in private studios and at the Municipal Art School of Belfort. Soon after my graduation, I received full scholarship for the School of Decorative Arts in Strasbourg. My answer to the exam committee for why I wanted to enroll in the interior architecture department was that “I needed to solve problems.” I don’t recall having had drafting or construction courses and later found myself quite unequiped when I did have to do my first professional internship in an architecture office, but what I learned was the ability to expose problems. I soon realized that if I were to go beyond an utilitarian discipline like architecture, I could create questions without having to offer a permanent solution. This notion of permanence, or rather its antonyms such as variability, instability, alterability and fluidity are the core of my work as they imply a constant remise en cause.

And this brings me to my (current) conception of beauty, constantly debating Augustine’s question of “whether things are beautiful because they give delight, or whether they give delight because they are beautiful”, or simply put, between the effect or the origin of beauty. Having had a classical education, I can’t deny my appreciation for harmonious proportions sometimes expressed in mathematical ratios i. e. the Golden Section or the canonical sculpture, but these place beauty as something purely objective and I must concede to the emotional effect of beauty, often associated with pleasure. A perfect balance is when I neither attribute beauty exclusively to the object or the subject, but to the relation between them and even more also to the situation and environment in which they are both linked.

The question is, can we still speak of the aesthetic experience in terms of beauty-that is a set of established criteria to judge a work? What I find more attractive, is not beauty per se, but the parameters that define it.

P: Your works convey a coherent sense of unity, that rejects any conventional classification. Would you like to tell to our readers something about your process and set up? In particular, are your works conceived and created gesturally, instinctively? Or do you methodically transpose geometric schemes?

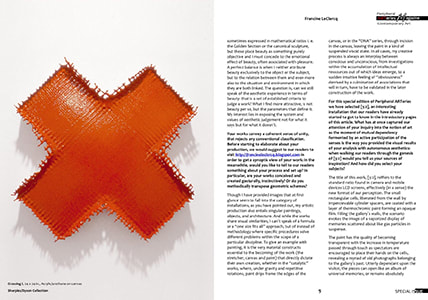

FL: Though I have provided images that at first glance seem to fall into the category of installations, and as you have pointed out, my artistic production also entails singular paintings, objects, and architecture. And while the works share visual similarities, I can’t speak of a formula or a “one size fits all” approach, but of instead of methodology where specific procedures solve different problems within the scope of a particular discipline. To give an example with painting, it is the very material constructs essential to the becoming of the work (the stretcher, canvas and paint) that directly dictate their own creation, whether in the “catalytic”works (1), where, under gravity and repetitive rotations, paint drips frame the edges of the canvas, or in the “DNA” series (2), through incision in the canvas, leaving the paint in a kind of suspended viscid state.

In all cases, my creative process is always an interplay between conscious and unconscious, from investigations within the accumulation of intellectual resources out of which ideas emerge, to a sudden intuitive feeling of “obviousness” derived by a culmination of associations that will in turn, have to be validated in the later construction of the work.

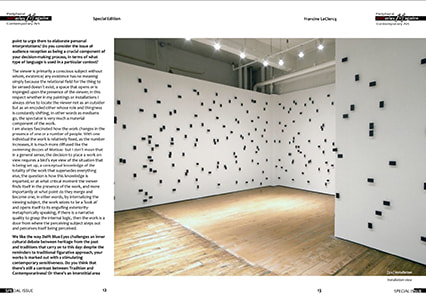

P: For this special edition of Peripheral ARTeries we have selected [3:2] (3). What has at once captured our attention of your inquiry into the notion of art as the moment of mutual dependency fermented by an active participation of the senses is the way you provided the visual results of your analysis with autonomous aesthetics: when walking our readers through the genesis of [3:2] would you tell us your sources of inspiration? And how did you select your subjects?

FL: The title of this work, [3:2], refers to the standard ratio found in camera and mobile devices LCD screens, effectively (in a sense) the new format of our perception. The small rectangular cells, liberated from the wall by cylinder spacers, are coated with a layer of thermochromic paint forming an opaque film. Filling the gallery’s walls, the scenario evokes the image of a vaporized display of memories scattered about like gas particles in suspense. The paint has the quality of becoming transparent with the increase in temperature passed through touch as spectators are encouraged to place their hands on the cells, revealing a myriad of old photographs belonging to the gallery’s past. Utterly depandant upon the visitor, the pieces can open like an album of universal memories, or remains absolutely abstract and unapproachable. Citing the exact measure of our portable mirrors and opposing analogue photographs to them, the works via the concept of traditional painting, expose the ephemeral nature of the novel perception. Furthermore, it asks to challenge the role of the artist as an image maker by transferring it to the viewers. Hence the gallery’s classic role as a match making box between the subject and the object, the see-er and the see-ee, employed to facilitate a tête-à-tête with this contemporary condition and restore, however temporarily an atmosphere of sensation or the sensible.

P: Your works address the viewers to challenge their perceptual parameters and allow an open reading, with a wide variety of associative possibilities. The power of visual arts in the contemporary age is enormous: at the same time, the role of the viewer’s disposition and attitude is equally important. Both our minds and our bodies need to actively participate in the experience of contemplating a piece of art: it demands your total attention and a particular kind of effort—it’s almost a commitment. What do you think about the role of the viewer? Are you particularly interested if you try to achieve to trigger the viewers’ perception as starting point to urge them to elaborate personal interpretations?

FL: The viewer is primarily a conscious subject without whom, existence/ any existence has no meaning simply because the relational field for the thing to be sensed doesn’t exist, a space that opens or is impinged upon the presence of the viewer; in this respect whether in my paintings or installations I always strive to locate the viewer not as an outsider but as an encoded other whose role and thingness is constantly shifting, in other words as mediums go, the spectator is very much a material component of the work. I am always fascinated how the work changes in the presence of one or a number of people. With one individual the work is relatively fixed, as the number increases, it is much more diffused like the swimming décors of Matisse- but I don’t mean that in a general sense, the decision to place a work on view requires a bird’s eye view of the situation that is being set up, a conceptual knowledge of the totality of the work that supersedes everything else, the question is how this knowledge is imparted, or at what critical moment the viewer finds itself in the presence of the work, and more importantly at what point do they merge and become one; in other words, by internalizing the viewing subject, the work seizes to be a ‘look at’ and opens itself to its engulfing exteriority- metaphorically speaking, if there is a narrative quality to grasp the internal logic, then the work is a door from where the perceiving subject steps out and perceives itself being perceived.

P: We like the way Delft Blue Eyes (4) challenges an inner cultural debate between heritage from the past and traditions that carry on to this day: despite the reminders to traditional figurative approach, your works is marked out with a stimulating contemporary sensitiveness. Do you think that there’s still a contrast between Tradition and Contemporariness? Or there’s an interstitial area where these apparently opposite elements could produce a proficient synergy?

FL: If history is an indication, there is nothing more traditional than the will to progress- which is to say despite its connotations, the longevity of tradition is dependent on the tensions between a long held belief and emerging concepts that constitute a new era- to which it must adapt and evolve. With Delft Blue Eyes, we (myself and my partner Ali Soltani) had to work with the collections of Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, an institution dedicated to historical works and crafts belonging to Dutch culture. The competition called for a contemporary object or work corresponding to a particular collection selected by the participants, so the notions of present and past (or a former present) and with it the manifest issue of a particular culture belonging to its respective epoch, defined the basis of the work- that is the insertion of something in time which is an uninterrupted continuum within the full breadth of unfolding historicity. Perceived in this way history is no longer a compilation of linear succession of distant events, and instead an instantaneous landscape of intensities marked by the peculiarities of a given time that could be interchangeably linked. We took the image of 17th Century Delftware plaques which was the high craft of the period and grafted it onto non-prescriptive contact lenses. Both are products that have flourished because of high demand and thus emblematic of their respective culture- on the one hand a product of the Dutch Golden Age characterized by its distinctly tactile quality attained through the manual manipulation of firing and glazing earthenware- and on the other hand the intricacies of an impalpable digital age represented by a technological veil on the iris that like a chameleon as it were has become one with the object it is fixated on. Thus in the implicit fragility of a crossbred porcelain gaze as the site of perceptual happenstance, a reference was made to Marcel Duchamp’s notion of non retinal art and the Readymades both with respect to chance encounters and choice, and more importantly by the realization that the navigational path of modernity to progress doesn’t have to be one way, nor straight. What is at stake is the notion of progress itself.

P: I Am Your Labyrinth (5) provides the viewers with an intense, immersive experience and as you have remarked in your artist’s statement, your work focuses on a complementary dialogue between materiality, content, the exhibition space, and the encounter with the viewer: how do you see the relationship between public sphere and the role of art in public space? In particular, how much do you consider the immersive nature of the viewing experience and how you see the relationship between environment and your work?

FL: It seems to me that with the advent of the internet, the domain of public sphere is shifting or I should say expanding from the exclusively collective spaces of streets and urban squares to the stealth realm of domestic life where it reincarnates as the virtual space of networks and the world wide web receding into a labyrinthine pixellation of some kind of media screen. On the other hand the casual urbanite is entrapped within a maze of partitioned institutions each catering to a different purpose with relative sufficiency, but the notions of the institution and the public remain at large and whether or not our relationship with art in this artificial construct is tenable. In this sense the reappearance of Ariadne as the eternal liberator that could offer us a way out, served as a narrative geared towards a critic of how we see and experience art and the whole machinery of its production. As the gallery space was being shared with another artist the construction of a 1:6 scale model of the gallery space not only compensated for the remaining area for the fully site specific installation, it effectively served as a gyrating crux through which the white cube imploded and expanded out, and blurred the normative distinctions between the perceptual and conceptual space. Similarly by incorporating the administrative aspects of the gallery and its reliance on infrastructure in organizing an event such as the invitation cards which were numbered and the mailing stamps that depicted my images of Ariadne, an attempt was made to reach beyond the confines of the gallery space and re-frame our notions of perception through an installation at large.

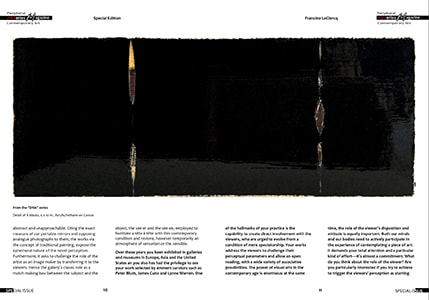

P: Despite to clear references to perceptual reality your visual vocabulary, as reveals the interesting Mise en [s]cène (6), has a very ambivalent quality. How do you view the concepts of the real and the imagined playing out within your works? How would you define the relationship between abstraction and representation in your practice?

FL: If you consider the notion of mise-en scène in set design, it consists of the staging of actors on a scene where its formal qualities is founded on a narrative that follows the telling of a story, a theatrical or cinematic likelihood that is mounted in front of a seating audience some distance away. What it shares with other arts is that it posits itself to be seen, designed to captivate the attention of a viewer, it relies in more or lesser degrees on some credence that is conveyed by content, structure, or both. What interests me however is the cross section of this business of viewing, that (emotional) field that holds the two parts, the viewer and the viewed glued to each other. To speak of the real, some years ago I saw a film by Abbas Kiarostami called Shirin in which the camera is turned to the viewers watching some epic Persian love story. We, the real viewers see the movie directly but we perceive the love story obliquely, guessing, through the contorted faces of its audience. I said real because at the end that is all there is, the question isn’t so much what we are looking at, rather how we are seeing it which I take to be the mise-en scène in my work. The Mise en [S]cène that you refer to, in its literal translation: To put on view- with a bracketed “S” before cène- (French for Il Cenacolo /The Last Supper of Leonardo daVinci), is an installation consisting of six panels that roughly add up to the same size of the original mural which literally flaked off and is virtually non existent were it not because of the cosmetic mascara of its restorers. You could argue that thing on view is 500 years of kitsch making that draws its credibility from 15 minutes of allotted time given to thousands of visitors that line up to view it. My installation was about this condition of an absence that is summoned by the spectator as a full presence to fill a void as though in a séance. With respect to the above, if there is an element of representation or narrative in my work, I would say as far as I am concerned, it is tangential rather than figurative or illusionistic, this is as much true in my installations as in my paintings which are mostly the outcome of their material construct.

P: Narcissus (7) inquires into the notions of gaze and perception: we daresay that this stimulating work is about the experiment to make visible volatile phenomena: would you say that the way you provide the transient with sense of permanence allows you to create materiality of the immaterial?

FL: I would say perception has a materiality that is felt through a force which like a soul, is in itself unseen but acts through subjective and objective factors. As an artist I have to be sensitive to how I set up a field of attraction. Placement, trajectories and speeds of movement and approach are the primary concerns which help me to decide on a certain arrangement, this is as much true for my paintings as it is in my installations which by necessity share curatorial and choreographic aspects. It is not without risks since the narrative component of curatorial work can easily be confused and be passed for design. With Narcissus, there was the additional element of a referent deeply invested in psychoanalysis that rests not in the content but in the subjectivity of the viewer which is never accessible. On the other hand, the striking aspect of Caravaggio’s Narcissus insofar as it related to my preoccupation with painting, was the latently modern posture of a kneeling figure looking down, utterly immersed, not too unlike a painter mesmerized by a pool of paint on the floor, and quite in contrast with the usual upright viewer in front of the painting. So a choreographic idea presented itself whereas a hybrid viewer/painter submerged in a pitted blackness of paint as it were (the walls were painted black below the standard 60 inches eye level) and guided by some invisible force-field would have to echo the physical genuflect of the mythical character and by diverting its gaze downwards, restore the horizontality of the paintings’ production which were done on the floor of my studio.

P: British multidisciplinary artist Angela Bulloch once stated “that works of arts often continue to evolve after they have been realized, simply by the fact that they are conceived with an element of change, or an inherent potential for some kind of shift to occur”. Technology can be used to create innovative works, but innovation means not only to create works that haven’t been before, but especially to re-contextualize what already exists: do you think that the role of the artist has changed these days with the new global communications and the new sensibility created by new media?

FL: In a world increasingly consumed by computer screens and instantaneous telecommunications, I believe the main difference in perception is the absence of the original sense of aisthesis or apprehension by all senses due to the annihilation of locality, temporality and physical presence. Though I am attaching great importance to spatial phenomena directly interwined with current time experience, very interesting perceptual typologies are emerging through technology. To give an example, I just participated in a guerilla project consisting in uploading an artwork that would automatically be seen by anyone logging on a dedicated site but only if you were to be present at a specific geolocation and for as long as another image was uploaded by someone else. Here notions of duration, presence, institution, and censorship were totally challenged.

I have a sense that emerging concepts such as the increasing synchronicity between production, presentation and distribution, or the changing relationship between originals and copies among other, are going to influence the way artists work, from customizing originals, staging copies, or maybe, to just archiving the attempt to create.

P: Thanks a lot for your time and for sharing your thoughts, Francine. Finally, would you like to tell us readers something about your future projects? How do you see your work evolving?

FL: Thank you for your thorough questions. As for this last one, future is not something that I can predict. The work may take a path on its own and the question is how I will evolve with it.

Lately, I have been interested in “automatic object detection”, a image search tool on the internet. Images are represented as vectors preserving not only their visual information but also their semantic concepts. Playing around with one of my image (model of I am Your Labyrinth), I was able to see it matched with a filing cabinet and even bathroom fixtures! It is a little bit that dreaming where quite unexpected scenarios emerge and supply the subconscious.

I don’t quite know what form (if any) the work will take so I will leave it at that.

Art Reveal Magazine no.11

Cover and interview

December 2015, ISBN 97813672936729363564

Cover and interview

December 2015, ISBN 97813672936729363564

Vimeinen Ehtoollinen/ Francine LeClercq, Andy Wahrol, Pauno Pojolainen

2011, EAN 9789529982813

2011, EAN 9789529982813